Welcome to CogSci Unpacked, an exciting blog series dedicated to summarizing academic papers from the Cognitive Science, a CSS Journal. Our goal is to bridge the gap between academia and the broader public, fostering a better understanding of cognitive science and making it accessible and relatable to all. If you’re curious to dive even deeper, we invite you to explore the full academic paper.

People tend to have very strong views on controversial issues such as whether vaccines should be mandatory, or whether abortion should be legally permissible. A common claim in moral philosophy is that our views on these issues can change as a result of our reflecting on their consequences. Particularly, two common views on the effect of outcome-based, or consequentialist, reflection on people’s moral attitudes is that those might shift towards more progressive stances (e.g. Singer, 1981), or towards more consensus (e.g., Greene, 2014). But does reflecting on the consequences of real-world controversies actually shift moral opinions?

Testing the Power of Reflection

The effect of consequentialist reflection on people’s moral views has been tested in moral psychology using hypothetical scenarios. For instance, some researchers (Hannikainen & Rosas 2019) asked their participants to reflect on the consequences of hypothetical cases of moral transgressions, such as food hoarding. Thinking about the harmful consequences caused by hoarding increased moral condemnation in both Colombian and British participants. But what happens when the issue is a real-life ethical controversy rather than a hypothetical situation? Political psychologists have found that after reflecting on information about controversial political issues in American politics, such as tax cuts, participants tended to strengthen their views about such issues (Nyhan & Reifler, 2010). This raises an interesting question: can outcome-based reflection shift views on bioethical issues in a meaningful way?

In our two studies, we addressed this question by comparing the moral views of our participants on seven bioethical controversies before and after experimentally inducing a brief outcome-based reflection. First, we asked participants to express their moral views on statements related to these controversies. A week later, we asked them to reflect on the consequences of one of these issues, and to express their moral views about that issue (target item) and the remaining six (control items) again. For instance, in the case of the permissibility of abortion, participants were asked to reflect on the item “At what stage of human pregnancy is the fetus capable of experiencing pain?”. This question prompted participants to reflect on the potential harm-related consequences of the practice by reflecting on medical and psychological research concerning fetal pain. After this mandatory and brief consequentialist reflection, they were asked to share their moral views on the issue again. We then checked whether the consequentialist reflection had changed their moral views, compared to their responses a week earlier.

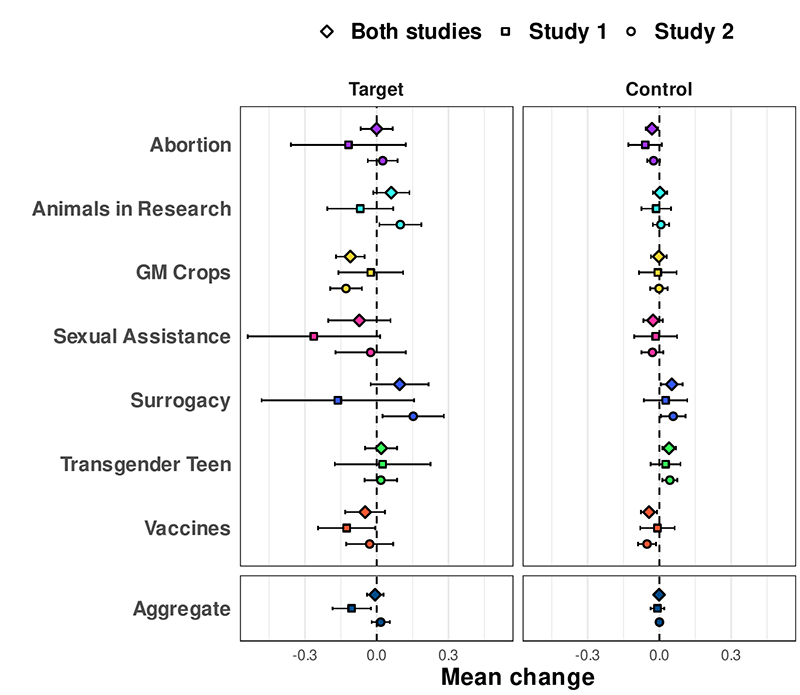

Figure 1. Mean change in attitudes toward the seven normative statements across the two sessions of Experiments 1 and 2, comparing target (reflected) and control (unreflected) items.

What We Found

Contrary to our expectations, a brief outcome-based reflection did not significantly shift participants’ views towards progressive stances, nor did it enhance consensus among them. Although our results from Experiment 1 suggest that briefly reflecting on the consequences of real-world ethical controversies shifted our participants’ views towards progressive stances on the target issues (those that they were asked to reflect about), this pattern was not replicated in Experiment 2 with a larger sample size (see Figure 1). Instead, participants’ views shifted equally towards progressive and conservative stances.These results align with recent research showing that reflection doesn’t always have a clear or consistent effect on moral judgment, even in hypothetical scenarios (Herec et al., 2022). On the other hand, our results might suggest fundamental differences in how we reason about hypothetical versus real-world moral dilemmas.

Overall, these findings highlight the complexity of moral reasoning in real-world controversies and the need for a nuanced understanding of how outcome-based, or consequentialist, reflection influences moral attitudes about real-world ethical controversies.

References

Greene, J. (2014). Moral tribes: Emotion, reason, and the gap between us and them. Penguin.

Hannikainen, I. R., & Rosas, A. (2019). Rationalization and reflection differentially modulate prior attitudes toward the purity domain. Cognitive Science, 43(6), e12747. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12747

Herec, J., Sykora, J., Brahmi, K., Vondracek, D., Dobesova, O., Smelik, M., … & Prochazka, J. (2022). Reflection and reasoning in moral judgment: Two preregistered replications of Paxton, Ungar, and Greene (2012). Cognitive Science, 46(7), e13168. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.13168

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2010). When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions. Political Behavior, 32(2), 303-330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9112-2

Singer, P. (1981). The expanding circle. Clarendon Press.